Catherine and Jeremy Broadway

When Dutch elm disease swept through southern Britain in the 1960s and 70s, over 90% of elms were lost; an estimated 25 million trees. A rogue fungus dispersed by bark beetles was the cause. Cath and Jerry Broadway told me there used to be many elm trees around Elm House Studio, their home in Child Okeford where the couple lovingly create handmade pottery and ceramic products, beautifully hand painted with designs inspired by nature. The elm trees have returned and Jerry informed me that as long as the hedgerows are kept well below 15 feet the saplings will thrive. The insect flies at that height so the smaller trees are safe. Passionate about passing on his extensive knowledge not only of pottery but also of the lovely countryside surrounding their home, he also coaches individual students in his spare time.

The current lockdown has given them both more opportunity for exercise, photography and simply time to ‘stand and stare’ at the masterpieces of nature – from a shattered puddle of ice to frosty seed heads in the hedgerows. Having nature on one’s doorstep, helps not only with lockdown but also a means of improving mental health and clinical depression. Describing it as similar to Churchill’s ‘black dog’, Jerry has personal knowledge of this. The structure, processes of glazing and different firings involved in throwing a pot have helped to give him the tools to cope.

“Artists are privileged people because they’re able to see the world in ways that perhaps other people cannot. That’s why it seems selfish to keep this skill to myself and why I always like to do some form of teaching. It almost feels like a moral responsibility. I dread that if art is not kept alive it will cease to enrich people’s lives. It’s so important for artists be approachable” he says, giving me an endearing example: “One day at the local fete I ran a workshop for children to experiment with clay. One little girl was working for a long time on her own, wetting and smoothing a small piece of the clay. She told me it was finished and I tentatively asked her what it was. ‘It’s a pond’ she said! So I suggested we place a little duck on it!”

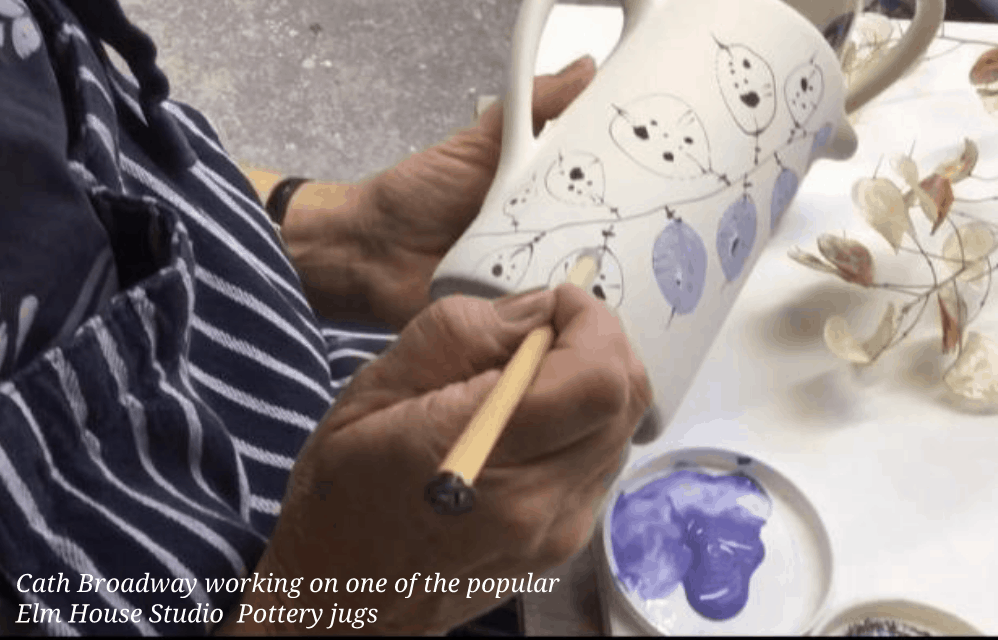

Cath attended Art College at Kingston, Surrey where she gained a first-class BA Honours Degree in Fine Art. She further developed her skills at Chelsea College of Art, gaining a Master’s Degree in the field of Fine Art and training as a printmaker. Her husband introduced her to the art of pottery and thus it became a true ‘marriage of convenience!’ The duo are complementary, each with their own distinctive approach. Cath’s artistry is in the imaginative surface decoration, whilst Jerry’s skills lie in the making and the chemistry of the glazing. She made an interesting comment: “A painter’s colours are ready made whereas a potter must mix and sieve his raw ingredients. Firing is also an art in itself, it brings life to the work. Potters often wonder why they put themselves through this. Ultimately it is to find the ideal balance between surface and form.”

However, they are now encouraging each other to take more risks and become less inhibited with their work. With Cath’s love of colour and line, she hopes to incorporate some of these new ideas into her mainstream production – for the enforced isolation has enabled a period of what Cath calls “bonkers experiments” in the studio. For example, Jerry showed me a pre glazed pot where he had taken electrical cable wire and road chippings (containing basalt and broken glass!) and was expecting them to melt into the glaze when fired in the kiln.

What can look random is carefully chosen. Potters are famous for guarding their recipes and Jerry admitted it would feel like cheating to buy in ready mixed glazes. Donning an alchemist’s hat, he has spent many years building up a series of precious notebooks for different recipes, some of which are 45 years old. “Just one glaze may have up to eight ingredients which must all be weighed, sieved and measured, including felspar, flint, talc, bone ash and china clay. All these recipe ingredients are carefully guarded secrets.” He is also very knowledgeable about the 4000 year history of pottery: traditional utilitarian Verwood and Harvest jugs which show the way in which studio pottery developed and became more personalised. “There was a sincerity and honesty in traditional pottery but it changed with the Industrial Revolution”. The Japanese and to a lesser extent the Chinese have always been esteemed potters. Bernard Leach born in 1887, although much influenced by the Japanese, heralded a revival and was known as the ‘Father of British studio pottery’. “However, today the final nail in the coffin is that the Chinese can now mass-produce cheap good quality pottery which looks hand-made.”

I was then introduced to the Japanese concept of Wabi-sabi. Its simplified meaning is ‘to take pleasure in the imperfect’. When a pot is taken from the kiln, the potter can accept the defects – perhaps leaving the fingerprints and ignoring something unexpected that has occurred during the process. It is a notion of appreciating beauty that is ‘imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete’ in nature. However, as Cath cautioned, “You have to know when to stop. Sometimes it can be frustrating when you work really hard in the studio and something comes out of the kiln that you were not expecting and the glazes are not quite right. There is a subtlety. It cannot be intentional but it is exciting.”

Jerry continued: “The programme for firings in the kiln must be just right. For example, a firing will go up from 0 to 200 degrees very gently to get rid of the moisture in the pot and to avoid blowing the pots apart. Further slow heating allows all the particles to melt together and it is taken up to 1000 degrees in the first firing. Then the glaze is mixed, added to the porous surface and the water is absorbed with the minerals staying on the surface. When the process works you know the effort has been worthwhile. When we make a pot we want to make something that is beautiful. It goes beyond functionality and purpose into art.”

Cath and Jerry believe that art should be affordable. “If you don’t encourage people to start admiring and enjoying art at a young age you exclude people. We’d rather make less money and have a customer who truly appreciates the work.” Customers can look out for their pottery in National Trust shops; First-View Gallery, Stourhead; Gallery in the Square, Dorchester; The Workhouse Chapel and hopefully during Dorset Art Weeks in 2021. We will all be in need of some ‘bonkers experiments’ by then!