During Britain’s Industrial Revolution, 4,000 miles of canal were developed in an astonishingly short time – but in the end, Dorset didn’t get any! Roger Guttridge details the local planning catastrophe.

As a veteran of canal holidays in the ’70s and ’80s, I’ve often wondered what Dorset would have been like had these arteries of the Industrial Revolution reached our county. They almost did: between 1796 and 1803, eight miles of the Dorset and Somerset Canal were constructed at the Somerset end.

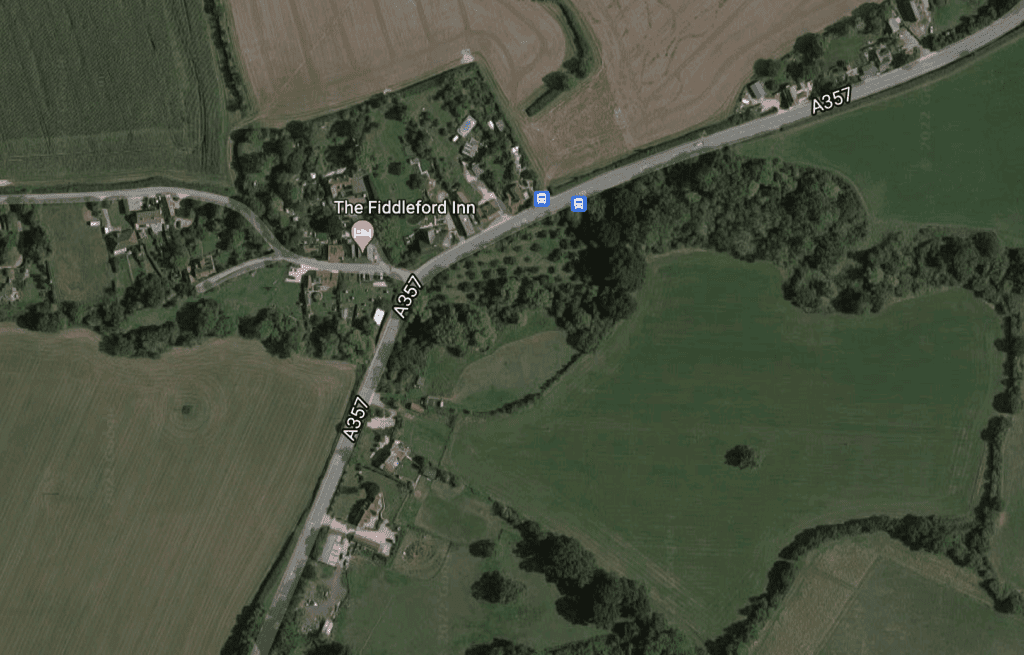

Had the ambitious project continued, parts of North Dorset would have been transformed, especially Fiddleford, where there were plans for an aqueduct fed by the Darknell Brook (see images, above).

Had they come to pass, the Fiddleford Inn or the former Traveller’s Rest, two doors away, might now be called the Narrowboat or the Boatman’s Rest.

The feasibility of a ‘Dorset and Somerset Inland Navigation’ was first discussed at a meeting in Wincanton’s Bear Inn in January 1793, when canal- mania was sweeping across the entire country.

In 80 years, 4,000 miles of canals were built, helping to transform both the national economy and local economies along their routes.

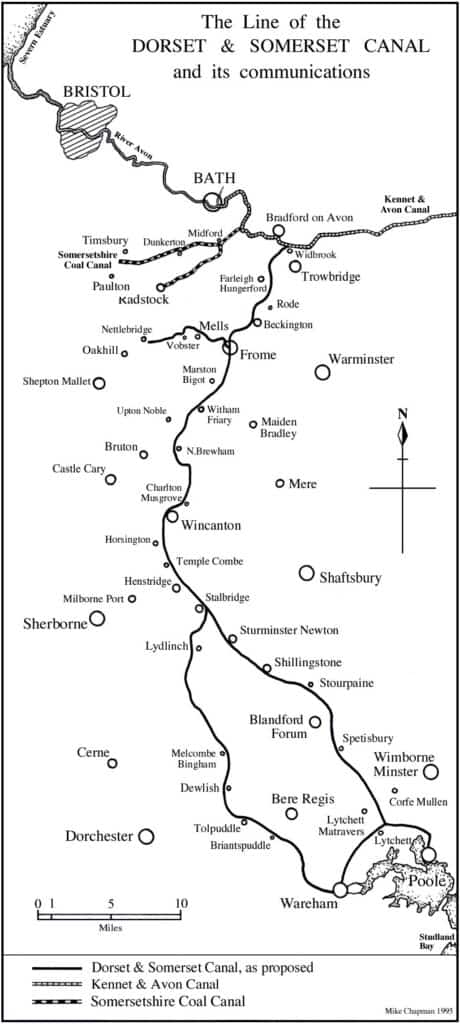

The local plan was to provide a waterway link between Poole and Bristol – an alternative to the long and hazardous voyage around Cornwall.

Huge network planned!

Supporters predicted a regular traffic in coal from the Bristol and Somerset coalfields, and Purbeck clay destined for the Staffordshire Potteries.

Other cargoes envisaged included freestone and lime from Somerset and timber, slate and wool from Dorset.

Initially there was great interest from investors with subscriptions greatly exceeding the prescribed minimum.

The proposed route ran from Bath to Frome (with a branch to the Mendip collieries) and on via Wincanton, Henstridge, Stalbridge, Sturminster Newton, Lydlinch, King’s Stag, Mappowder, Ansty, Puddletown and Wareham to Poole Harbour.

Wareham folk were supportive but a meeting at the Crown in Blandford insisted the canal would be more beneficial if it went from Sturminster Newton to Poole via Blandford and Wimborne.

Counting the cost

Robert Whitworth, the project’s consulting engineer until he resigned in September 1793, favoured the Blandford option. His costing for the 37 miles from Freshford to Stalbridge was £100,234 (approximately £15,461,737 in 2021)

The remaining 33 miles to Poole had an estimated cost of £83,353.

The Blandford route was finally chosen in 1795 but with branches to Wareham and Hamworthy.

It seemed like the perfect compromise but there was still opposition from some landowners.

Lord Rivers insisted that ‘the canal did not proceed beyond some point betwixt Sturminster and Blandford, otherwise withholding his consent’.

In 1796 a drastic decision was taken to abandon the southern section, reducing the canal’s length to 48 miles and the cost to £146,018 (approx. £22,524,212 in 2021 terms).

Bizarrely, it would now terminate at Gain’s Cross, Shillingstone.

Catastrophe rocks the plan

With £73,000 already raised from shareholders, the necessary Act of Parliament was quickly obtained and received royal assent.

It gave the owners the right to draw water from any source within 2,000 yards of their canal and to create a junction with the Kennet and Avon, thus connecting to the national network.

Work on the Mendip collieries branch began in the summer of 1796.

A newspaper advertisement said progress was rapid, the public would soon experience the benefits of the canal and ‘part of it near the collieries is already completed and a barge was launched there on Monday’.

The advertisement proved to be hopelessly optimistic.

Of the original £70,000 pledged by prospective shareholders, only £58,000 materialised.

Over the next few years, partly due to the Napoleonic wars, the company lurched from crisis to crisis and only eight miles of canal were built. Progress was hampered and expenses increased by the rocky terrain.

Those eight miles alone required 28 bridges, three tunnels, an aqueduct, 11 grooved stop-gates, nine double stop-gates and three balance locks.

Construction ceased in 1803, when the last of the money ran out, although hopes lingered

on until the mid-1820s, when attempts were made to involve the canal company in plans for a railway covering the same route. It would be another 30 years before the rail link came to fruition.

By then the canal – originally described as ‘one of the best conceived undertakings ever designed for the counties of Dorset and Somerset’ – was reduced to an overgrown relic in the Somerset countryside.

The company’s records suffered an even worse fate when a bomb fell on Wincanton during World War Two.

Among the few surviving documents is the plan for the double-arched aqueduct at Fiddleford, shown opposite.

The picture also shows a ford where the stone bridge is today and two houses that still survive.

by Roger Guttridge

[…] insertion of brackets around my first reference to the ‘former Traveller’s Rest’ in my story on the Dorset and Somerset Canal gave the impression that this long- lost pub and the present-day Fiddleford Inn occupied the same […]