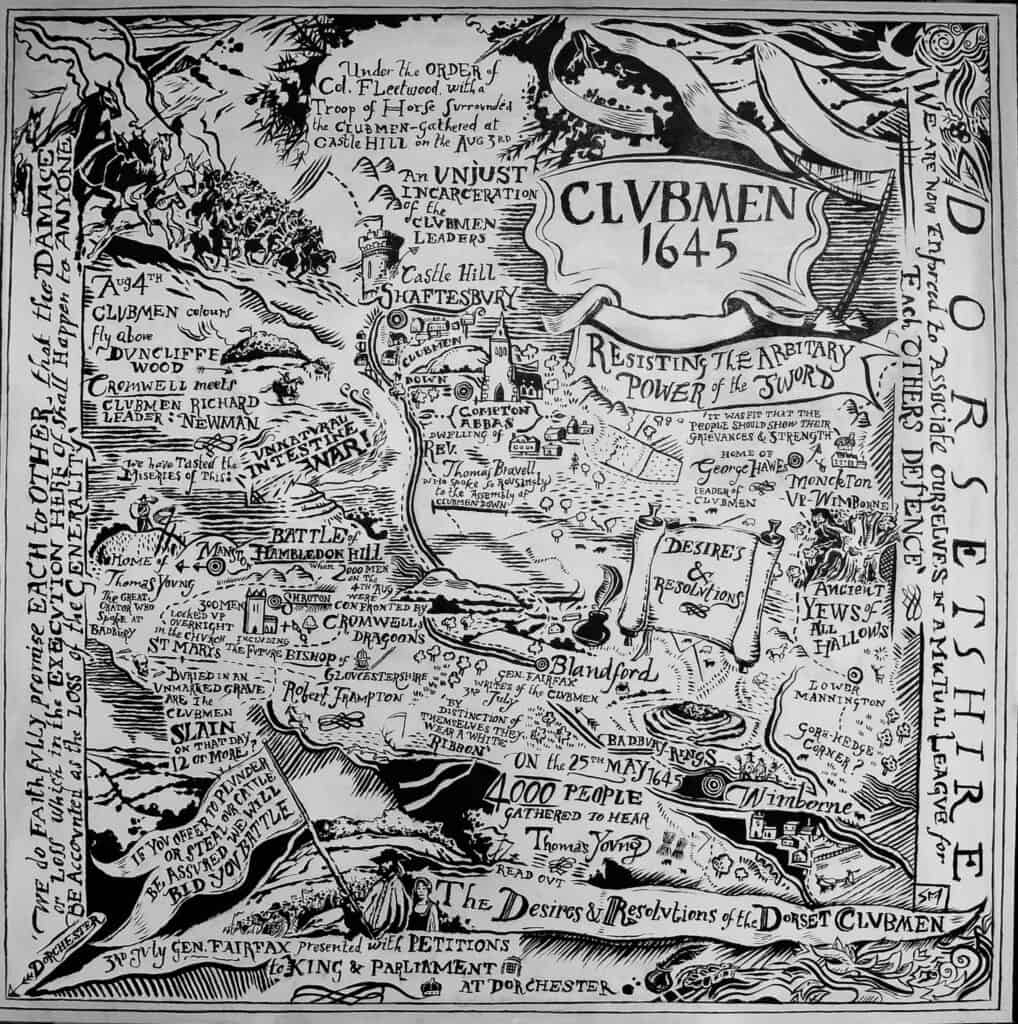

The fascinating history of compassion, bravery and pitched battle in Dorset during the Civil War is told by Rupert Hardy, chair of North Dorset CPRE.

Abbas, fought Cromwell and his Roundhead Dragoons, with up to 60 men killed as they eventually fled

People often forget how severely Dorset was impacted by the Civil War which started in earnest in 1642. The county lay between the Royalist strongholds in the West Country and those of the Roundheads in South East. Dorset was very divided with Sherborne and Blandford Royalist while Dorchester and Lyme Regis were strong supporters of Parliament.

There were repeated clashes and sieges, such as at Corfe Castle, where the brave Lady Bankes held out for years. However ,the largest pitched battle was at Hambledon Hill in 1645, and was fought between an army of Roundheads and a motley band of local farmers, called Clubmen, driven to defend their land and homes from the ravages of both Roundhead and Cavalier soldiers.

Indiscriminate plundering and looting by these troops in Dorset and other counties had gone on for several

years badly affecting rural communities, especially in the Vale. Soldiers were for the most part ill-paid and poorly disciplined, living off the land, although the formation of the New Model Army in 1645 improved things to some degree.

A white ribbon on their hats

In exasperation farmers formed local militias to defend themselves and their families. They were known as

Clubman, due to the rudimentary nature of their arms, including clubs and pitchforks.

They were often led by the local clergy, as well as gentry, while their ‘uniform’ was no more than a white ribbon on their hats as a sign that they were a neutral third party.

They did carry banners saying: “If you offer to plunder or take our cattel, be assured we will bid you battel!”.

The first notable sign of them in Dorset was in February 1645 when 1,000 gathered at Godmanstone, outside Dorchester, and killed a few Royalist soldiers. By May, Clubmen were organising themselves throughout the west of England, and 4,000 gathered on Clubmen’s Down near Fontmell Down to create

articles of covenant and organise groups of watchmen to guard against the soldiers who stole and plundered.

In June a similar large gathering took place at Badbury Rings calling for “an end to this civil and unnatural war within the Kingdom”. The next month a deputation of clerics and gentry presented parliamentarian General Sir Thomas Fairfax with a petition in Dorchester, which prompted him to promise them good discipline.

However, in August Fairfax started to besiege Sherborne Castle, but found his supply lines threatened by

Clubmen. He therefore sent troops, commanded by no less a figure than Oliver Cromwell, to Shaftesbury to

arrest their leaders as they presented a real threat to his Parliamentary forces.

Cromwell did this, but then nearly faced a battle with Clubmen at nearby Duncliffe Hill. However, he managed to pacify them after an arduous climb to the top of the hill to meet their leaders, including

Richard Newman of Fifehead Magdalen.

Cooper’s original, in watercolour on vellum, is the size of a 50p piece but miraculously detailed – from the bald patch, creased

forehead and roughened cheeks to the jowly five o’clock shadow. When Cromwell came to Cooper’s studio, he gave the famous

order for less flattery and more accuracy

Battle of Hambledon Hill

A few days later the Clubman had regrouped on Hambledon Hill. They numbered 3-4,000 and were led by Newman and the Rev. Thomas Bravel of Compton Abbas. They were determined to make a stand against the Roundhead dragoons, while Cromwell thought it was time put an end to the threat they posed to his supply lines. He attempted to negotiate but was met with a hail of bullets which killed two of his men. The Clubmen had dug trenches and used the existing Iron Age banks and ditches. They were expecting a frontal attack,

but Cromwell outwitted them by sending 50 dragoons to charge their rear as he attacked the front. The

Clubmen took one look at the dragoons bearing down on them and most fled down the hill in panic, with up

to 60 killed. Three hundred were locked up overnight at Shroton, including four “malignant priests”. Cromwell gave them a lecture and then dismissed them calling them “poor silly creatures”. A Roundhead helmet hung from the church there until quite recently as a reminder.

The Clubmen might have had greater success had they been more united. Part of this was related to the

army of occupation they feared more. Langport Clubmen only experienced the ravages of Royalists, so they actually helped the Roundhead army in 1645 while those in Dorset and Wiltshire feared both armies.

Rebellion by the ‘common man’

There were more Clubmen risings later in the year but The Battle of Hambledon Hill was the last time they presented a real threat to either army. It would be wrong to underestimate them though. The failure of either the King or Parliament to agree a peace treaty only served to increase tension as plundering continued, and

gave further motivation to the Clubmen. After Hambledon these were demonstrated largely through physical demonstrations and print culture, particularly in pamphlets.

Joshua Sprigg, chaplain to General Fairfax, summed it up well, if the Clubmen rising “had not been crushed in the egg, it had on an instant run all over the kingdom”. Some historians have sought to attribute revolutionary tendencies to them, but this is simply not true.

They mostly wanted a return to the status quo before the war, but they are remembered as early instigators of rebellion by the ‘common man’ and their example of community self-defence was inspirational.

If you’re keen to learn more, the book ‘CLUBMEN 1645, Neutralism in a Revolution’ by local author Haydn

Wheeler is available here.

The English Civil War 1642-9

The conflict started when King Charles 1, believing he had the divine right to rule, was confronted by ‘commoners’ in Parliament who demanded a more democratic (by the then standards) rule of law. The impasse led to open conflict with the Royalist army, supporters of the king, opposing the ‘Roundheads’, supporters of Parliament The conflict ended with the trial of the monarch ‘for treason’ after ‘the will of the common man’ triumphed. Found ‘guilty’, Charles was beheaded outside The Banqueting Hall, Westminster, on January 30th 1649 – almost exactly 144 years before the French revolutionaries beheaded Louis XV1.

RURAL MATTERS – monthly column from the CPRE