From wartime skies to quiet evenings of music – meet Jim Freer, the centenarian who says there’s still plenty more to learn yet

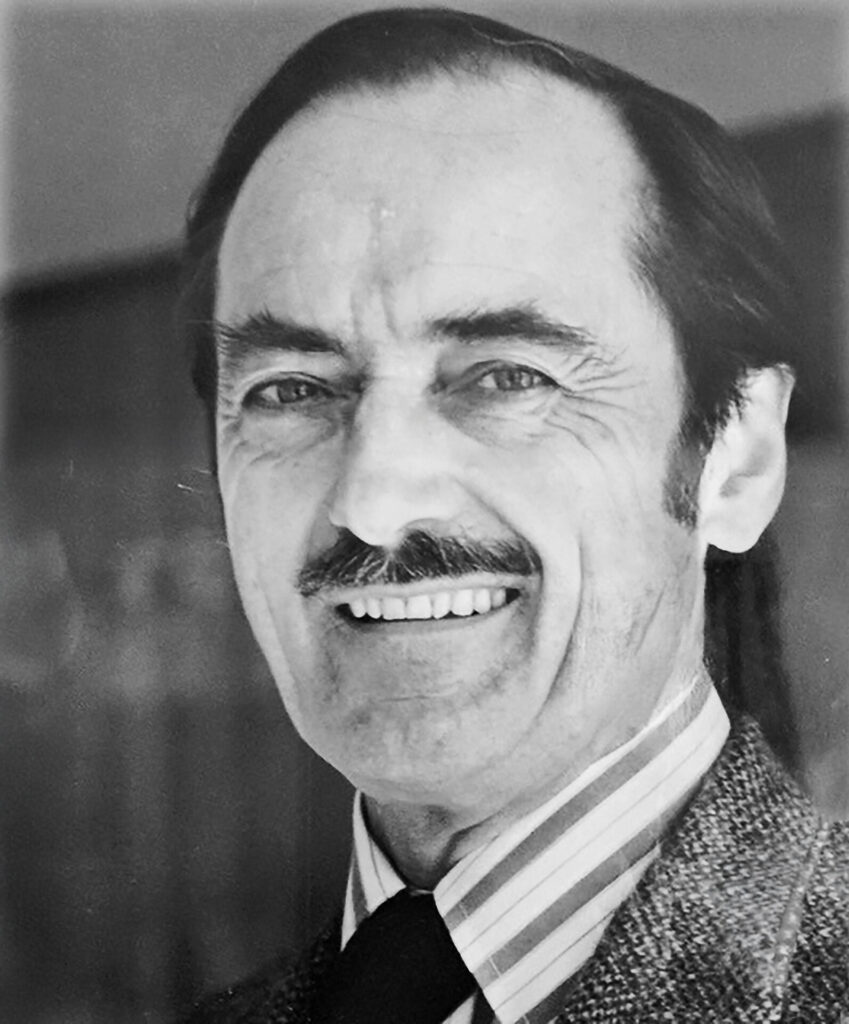

Jim Freer will turn 100 on 16th April. Sitting in his sunlit room in a Sturminster Newton care home, his eyes are bright and sharp, belying the century he’s about to complete. He speaks with warmth, wit and the clear recall of a man who’s lived a long life – and paid attention to every detail along the way.

Born in Desborough, Northamptonshire, Jim came from a family of shoemakers and dairymen. His first job was as a junior draftsman at the Harborough Aircraft Company in 1940. ‘I was 17 and a half. I made the tea, walked the dog – the usual start for someone at the bottom. But we were making engine frames for Lancaster bombers, so you knew it mattered.’

When he was old enough, Jim joined the RAF. ‘I told the selection board I wanted to fly. They said I wasn’t quite right for a pilot or bomb aimer, but the new four-engined bombers needed flight engineers. So that was me.

‘I had a long course at the Technical Training Command section on airframes and engines and so on and so forth … and then, finally, the flying bit actually started.’

He joined a Canadian crew in Yorkshire – six group Bomber Command of the RCAF – with six young men already trained on twin-engine bombers. ‘We did a short training course on the Halifax bombers, and then we were considered experienced enough to start on operations. I was very surprised that someone who was hardly 19 years old was suddenly put in charge of 6,500 horsepower. I thought, “God, can I do this?” But my crew were amazing. Every one of them had volunteered to come over from Canada. And we made a team – teamwork was vital. We were scared, but … I can’t explain it, it just didn’t break us down. I think we stuck to it because we were a good team, and that makes all the difference.

‘We were perhaps fortunate that we missed most bits of flak. We were caught in lights once or twice, that was a troublesome time … but the worst was on the real serious bombing raids that “Bomber” Harris demanded, where he had up to 1,000 aircraft over. You had a good chance of being bombed yourself, with aircraft at different levels and so on, and you never knew the accuracy of the navigation either. But somehow they missed us all. We were lucky. We were lucky.’

Flying post

Jim’s crew flew 33 operations over Germany and France. ‘The official record says 34, but one didn’t continue. We were called back, so we don’t count that one.’

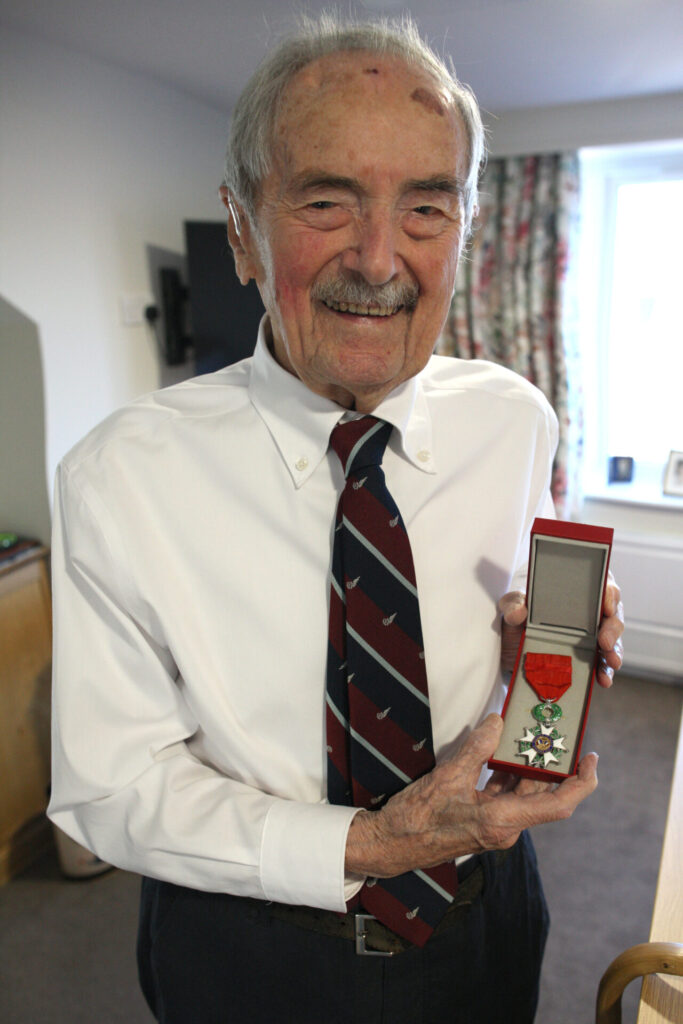

They were in the air on D-Day, supporting Canadian troops as they pushed into Caen. ‘I got a French medal for that. But lots of people did what they could to get France out of German occupation. So, yes, I did my bit. But hero? No.

‘There were lots of real heroes. I’ll put it that way. People that were shot down or taken prisoner or put in prisoner-of-war camps, you know, All sorts of things could happen to people. We were lucky.’

Jim stayed in touch with some of his Canadian crewmates for decades. ‘One or two even came back to visit. I’m still in touch with the daughter of our rear gunner. She’s in Ontario now.’

After the war in Europe ended, Jim was put on a code and cipher course and then posted to the Far East as a signals officer. ‘When we got there, they said, “I don’t know why they sent code and cipher officers, we’ve got more than we need.” It was right at the end of the war with Japan, and immediately that happened, of course, most of the military wanted to get back home. They didn’t want to be there anymore. Morale broke down, really seriously broke down. So Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten, who was senior military personnel man in the Far East at the time, said: “We’ve got to improve our postal service with the UK, so that at least people can get letters. That will help them to accept the fact that they’ve got to stay until we can move them all out.”

‘They needed a unit to look after that, so I was seconded to RAF Post. We had a number of Avro York freight aircraft that we could use for mail carrying from Calcutta and Delhi and Bombay, and we could then get all the mail together as quickly as possible, and onto these aircraft, over to the UK, and then delivered. The objective was three days transmission time, and we did achieve it eventually. It was an enjoyable, different job, still to do with aircraft – and better than being shot at!’

And so to Dorset

Once demobbed, Jim returned to civilian life – rejoining his old company, now relocated to Maidenhead. ‘The managing director was an ex-Group Captain. That probably helped my recruitment! I started with drawing and design and so on, back in the old days when we had a big drawing board and a T square … it’s all computers now of course. I did that for a couple of years or so, and then I got itchy feet, and got a job as buyer for the company, buying materials. And then I went to being in charge of production as well, and eventually I ended up in 1980 as production director. And I felt, well, you know, there’s not much more I can do here, I don’t think. I was about mid 50s, then. So I applied around for quite a few jobs, and I secured a job with Alan Cobham Engineering at Blandford. We were producing large filters for the Navy. We made equipment for the Coal Board, filters for their grinding machines, and we made flow valves … Really it was a civil version of Cobham Ltd, as it was their parent company, and we linked in to their work quite a bit. We were very much involved in the Falklands war. I spent eight years there, before I retired to Child Okeford.’

A first marriage to Pat in 1950 had brought 60 happy years together, although they never had children. ‘I’ve had 30-odd years of retirement. I got involved with Blandford Museum, with social things in the village, the gardeners club, and this and that … we just went out and about and enjoyed things. We really loved living in Child Okeford. It’s a nice village. Unfortunately, now, most of my contemporaries are dead – you lose your mates. Pat died in 2017.

‘In 2019 I married Val, a long-time family friend, and we had a lovely few years together before I moved here.’

“Here” is Newstone House, and it has become a sociable home for Jim. ‘I think my parents did a very good job. They put their genes together – or took their jeans off , I suppose – and created something that was OK. I haven’t got any serious physical problems. I use a stick, and I can’t walk very well. But I think I’m alright up top!

‘I’m with younger people all the time now, and I’m seeing life in different areas. I often go down to chat with the dementia residents – lots of them have had such interesting lives. Sometimes they’ll just go quiet. Other times, we really talk. It’s good for both of us.’

Jim’s eyesight has suffered in recent years – macular degeneration has left him unable to read. ‘But I can still see the TV if I sit close. I love music, and oddly enough, I take the hearing aids out to listen to it because I get a better sound. There’s always a little bit of distortion in these things that you can’t avoid. They can’t produce a bit of metal or plastic that can do what the ear originally did.

‘I listen to a wide variety, though I think you can take the music of the last 40 years out of my brain, because I can’t cope with that. But you know, probably from wartime up until the 80s, that sort of era, easy listening, or that sort of thing. Chopin and Beethoven and composers of that time and type. Every evening I’ll listen to a couple of hours of music. I’m quite happy with that.’

Still learning

Over his 100 years, Jim has witnessed extraordinary change – but it’s the pace of it that strikes him most. ‘Oh yes, indeed, gosh. From seeing the early motor cars to now, and then the speed of change over the last period has been fantastic. The digital world is incredible … I can cope with an iPad, and that’s about my lot, really! But though it all, the main thing is still, I think, to be with people.’

He says flying during the war was the hardest thing he’s ever done. ‘I didn’t think I could really do what they asked me to do … but I did it. I always felt I wasn’t on top of the job. I was doing it, but I felt … “you know, there could be something happening here, and I haven’t worked out what.” It was a difficult period – much more difficult than any other period in my life.’

And if his century of living has taught him one message for the world?

‘It doesn’t sound much, really, but I’d say, “Be nice to people”. I think it’s infectious. If somebody smiles at you first thing in the morning, it does something to you, and you smile back. And if that attitude goes on through the days and the months and the years and so on, you’ll find you’re living life in quite a nice way.’

Jim insists he’s not a hero – just lucky. But behind that modesty lies a lifetime of service, resilience and quiet decency.

‘I think I’ve been lucky. And I’ve had a good life. I don’t really have any ambitions now … Well, I suppose I have, actually. I want to enjoy life with people. And there’s always something that’s new to see or to learn.’