From a burgage plot to the woman who installed plumbing– looking back at the evolving centuries of stories of Wimborne’s historic museum

As readers of The BV will know, the museum on Wimborne’s High Street has always been more than just a building. It’s a place where East Dorset’s stories live on – from grocers and ironmongers to wartime friendships and Victorian silks. And while the name above the door may have changed, the spirit inside remains deeply rooted in the town’s history.

Biggest on the High Street

The house itself dates back to the late 1200s, when it first appeared as a “burgage” plot – land leased by the Lord of the Manor to a local burgess (one of the town’s wealthier residents).

It’s believed today’s building may sit on an even earlier structure, though no evidence has been uncovered … yet.

By the 1500s, a one-storey hall house fronted Wimborne’s main street. Over the next century, it grew: wings were added, a large central fireplace built and the entire structure was raised two storeys between 1625 and 1675. A map from this era shows it as the largest building on the High Street after the Minster.

In 1687 Stephen Bowdidge took on the lease, and his son John moved in. When Stephen died in 1694 his will carried a threat of disinheritance for his son if he failed to provide a legacy for his sister Elizabeth.

But by 1709, John Bowdidge had run up considerable debts and was forced to sell the lease on the house.

Thomas Barnes, a local cheesemonger, moved his business in, paying ten shillings, the equivalent of a week’s wage, for his part of the house.

Over the next three centuries, this High Street landmark moved through a number of

incarnations – the building has always been a constantly evolving space of business and domestic life.

In 1746 Christopher King took over the lease from the Barnes family, and he and his wife Elizabeth opened a shop selling wool, velvets and imported silks. The Kings enclosed the front courtyard and also installed sash windows on the first floor of the south wing.

When Christopher King died, he left his business interests in the property to Elizabeth, who swiftly had a new kitchen built and a new lead water pump and plumbing installed!

Elizabeth was succeeded by her and Christopher’s son, William, and on his death in 1790 the lease was taken on by William Butt, a draper and grocer. He lived and worked in the building until 1825, and under his care the house once more underwent extensive renovation, creating more living space on the first floor and additional business storage.

The Low empire

In 1837 William Low took on the lease of the main building and ran his stationers, bookshop, printing and tobacco business from the north wing (the south wing continues to be identified as a separate property). The former courtyard area became a grocer’s shop. The Lows built up a family empire: an 1846 tithe map of Wimborne shows William Low owning the main house, garden and orchard as well as other plots of land down to the river. The 1851 census lists William and his three sons in the household, all in different parts of the family business:

William Low (64) bookseller and grocer

William Low (34) printer

John Low (29) grocer

Edmund Low (20) bookseller

Jane Woodford (9) niece

William’s second son John inherited the estate on his father’s death in 1871. For reasons no one knows, the following year John Low closed the stationers business in the north wing, with instructions that the shop should not re-open in his lifetime.

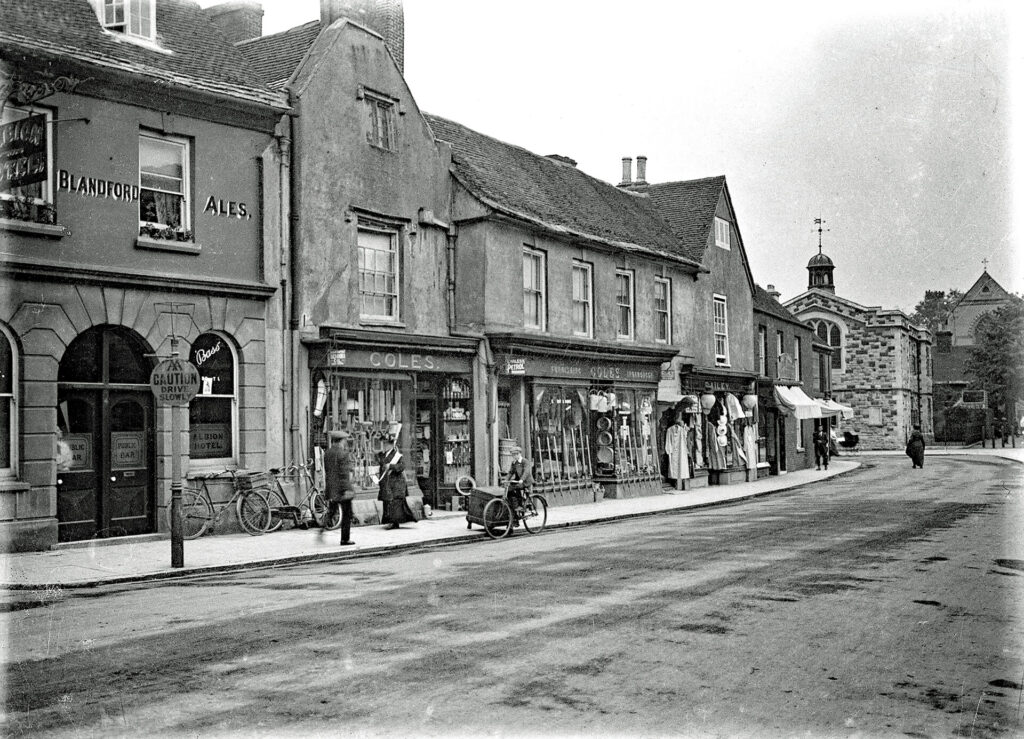

The same year, Thomas Coles – who had married John Low’s niece, Jane – took on the lease of the main premises and opened Coles Ironmongers. By the 1881 census, only the Coles family lived in the building, and in 1883, Thomas Coles bought the main property outright.

The Coles name would remain on the building for more than 70 years.

The Priest’s House

Interestingly, it was only in 1889 that the term Priest’s House first appeared on an Ordnance Survey map – and even then, it referred only to a part of the building. There’s no historical evidence of any priests living there, and the name has always been more evocative than accurate!

In 1901, John Low – the original owner of the stationery shop – died. In the same year, Tom Coles (junior) married Blanche Cox, the butcher’s daughter.

They took over the stationer’s shop – and they found all the old original stock still inside, including a large collection of Valentine’s and Christmas cards. Tom expanded the family’s ironmongery shop into the old stationer’s premises.

Tom and Blanche’s daughter Hilda was born in 1907.

During the 1930s, Barak Abley opened a gentleman’s outfitters in the separate south wing building, and his daughter Mary became a firm and lifelong friend of Hilda Coles. They both served in the Women’s Royal Naval Service in Invergordon, Scotland during World War Two.

A new chapter

In 1953, Tom Coles died, and Hilda took over the family ironmongers. Less than a decade later, in 1962, the building began its newest chapter – as a museum. Hilda Coles, known to all as Mick, closed the ironmonger’s and offered the ground floor to Wimborne Historical Society. Some locals were unimpressed. “What Wimborne needs,” they insisted, “is more shops – not a dusty old museum.”

But Hilda had vision – and conviction. On opening day alone, more than 1,000 people came through the doors. Many exhibits were curated from the old shop stock – thanks to John Low, the museum has one of the finest collections of Victorian Valentine’s cards in the country – and a vast collection of local artefacts that had long been waiting in storage for a museum of their own.

Through the decades, the museum has grown – both in scope and in stature.

In 1990, three years after Hilda’s death, a major restoration added ten exhibition rooms. In 2012, National Lottery funding enabled the creation of the Hilda Coles Open Learning Centre, with its tea room, study space and collections storage.

Museum of East Dorset

After 300 years of being split up and owned by different families and businesses, in 2020 the town house was finally reunited. It also underwent yet another modernisation, bringing the museum into the 21st century with purpose-made, museum-grade display cabinets, environmental controls and improved access for the disabled. After a full-scale £1.8 million revitalisation – again, largely funded through grants and national support – the museum reopened as the Museum of East Dorset. The new name, like the refurbishment, was thoughtfully chosen. As chairman of the Board of Trustees David Morgan explained at the time:

‘Letting go of the name Priest’s House Museum was a decision we came to after a great deal of consideration. While it was well known – even well-loved – locally, it did not resonate outside the town and the religious connotations were confusing visitors.

‘The name Museum of East Dorset reflects the museum’s collections area, and celebrates its important role curating, celebrating and sharing the history of the wider region.’

That broader scope is key. The museum’s collections now include more than 35,000 items – from archaeological finds to rural craft tools, period clothing to childhood toys – all gathered from across the towns and villages of East Dorset.

It’s not just a Wimborne story … it’s a regional one.

Today, the Museum of East Dorset is a blend of its long heritage and modern engagement. Its new logo – an echo of the old Coles signage – and dark green walls echo the house’s past while embracing its future. In Wimborne, a house that began as a simple burgage plot 800 years ago continues to serve its community – just as it always has.

sponsored by The Museum of East Dorset